Jaeyeon Choe

Bournemouth University

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised public awareness of the many dimensions of wellness. Following the World Health Organization, wellness may be understood as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Wellness may also be understood as an orientation toward optimising one’s health and well-being, in which body, mind and spirit are integrated in a holistic way, so as to live more fully within the human and natural community. COVID-19 has had a deleterious effect on all of these aspects of wellness. There are reports of the adverse economic impacts on people’s lives, greater stress due to lockdowns and restrictions, and impacts on those who lost friends and family to the virus. There are also ongoing and long-lasting consequences of contracting and recovering from the virus itself.

During the lockdown period, individuals have developed home-based wellness strategies such as gardening, cooking, baking and exploring local parks, and there has been skyrocketing interest in home yoga, yoga for kids and mindfulness on YouTube and search engine queries. During a recent webinar entitled “Wellness and spiritual tourism in a post COVID-19 world?”, Dr. Brooke Schedneck noted that meditation teachers in Chiang Mai, Thailand, have doubled their work-load with off-line teaching and Zoom mindfulness sessions. They are busier than ever!

Tourism experts and commentators have been reporting that there will be a big increase in travel to ‘wellness destinations’ as lockdowns ease. People are pursuing wellness tourism activities for their mental health during furlough, searching for new ways to be well, and reflecting on ‘new’ meanings of life after job losses. For example, some travel experts predict that “many people will want and need immunity-boosting escapes for preventative or restorative reasons.”

Will wellness tourism be more popular in a post COVID-19 world?

This was the question that four international scholars tackled during the webinar.

While wellness tourism was already a growing sector of the tourism industry, destinations and businesses anticipate new business opportunities in the post-COVID context. Wellness tourism involves holistic perspectives and activities (i.e., yoga, mindfulness and walking in nature) that help enhance the balance between body-mind-spirit. Spirituality is at the core of much of wellness tourism. Travelers seek relaxation as they confront the self and re-negotiate their place in the world and relationships to others. Under the wellness tourism category, spiritual tourism can be seen as producing well-being, including psychological centering of the mind and social connection with a community of believers. It is also seen as a reflexive well-being intervention, driven by the sense that some aspects of everyday life need improving. It is oriented towards the space of non-work and away from home, where such problems can be given full attention.

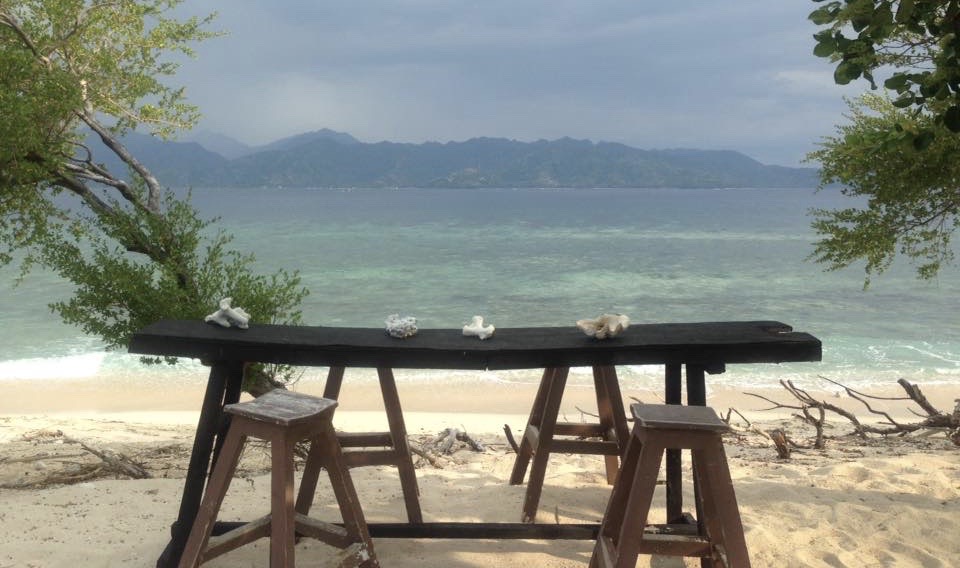

Whilst wellness tourism has a broader scope including medical and health tourism, spiritual tourism focuses on cultivating mental well-being. However, I remember that during my fieldwork in Bali in 2019, my Balinese colleague, Dr. Luh Putu Mahyuni, argued that spirituality should be a broader concept than wellness. During the webinar, Dr. Mahyuni noted that “Wellness tourism is about holistic well-being, not physical health. For Balinese, herbal medicine comes before seeing a doctor, and connecting to nature is key to wellness. Yoga and meditation are good for holistic well-being including body-mind-soul.” Physical ailments might be seen as deriving from spiritual problems in some cultures, with spirituality seen as affecting all aspects of life. Even during the pandemic, people might dwell more on the spiritual side of their lives. Dr. Mahyuni also emphasised that “In post-COVID Bali, there will be more domestic tourism. The Balinese people have also been returning to their ‘original’ lifestyle and to work in farms.” Dr. Mahyuni also noted that locals are relaxing in the mountain and at the beach, and reconnecting to nature and culture again. “I see there will be more eco- and community- based tourism,” says Dr. Mahyuni.

Dr. Schedneck, who has spent extensive time in Chiang Mai, Thailand also mentioned that Thai local people have different ideas about wellness tourism in comparison to Western travellers. For instance, different understandings of meditation lead locals and Western tourists to engage in different wellness and spiritual tourism activities. Western tourists often visit retreat centres in Chiang Mai to re-charge from busy lives. Buddhist monks invite the interaction, but they offer to help tourists to work on their problems at a deeper level, which can lead to self-transformation.

Dr. Michael Di Giovine noted that there will be greater demand for domestic tourism within the Western world. Wellness tourism is not all about Western travellers visiting less developed Asian destinations. He noted that because of travel restrictions as well as fears for of COVID-19, there seems to be a nascent trend of taking short-term, local retreats. Domestic tourists may begin to appreciate local ‘wellness’ resources such as walking in local parks or hiking and fishing in nearby rural areas. He noted that local-based “cocoon tourism” might re-emerge, where people travel to places relatively close by and stay outside in nature. This might include elements such as agri-tourism, but contain more wellness activities or pursuits.

Domestic tourism also includes those local people in destinations such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia, which has long been seen as a wellness playground for foreign tourists. Based on new meanings and appreciation of life, as well as the lack of international tourists, people are reconnecting to local spiritual resources. Overall, the four international scholars during the webinar noted that they see new or different spiritual or wellness activities emerging as well as searches for, and the development of new spiritual destinations.

Overall, the four international scholars during the webinar noted that they see new or different spiritual or wellness activities emerging as well as searches for, and the development of new spiritual destinations.

How can destinations prepare for the ‘new normal’?

I hope that there might be new opportunities to develop community-based wellness tourism businesses in rural and remote areas. As people search for small-scale and quieter destinations for longer stays, there may be new opportunities for tourism businesses in rural villages in the Global South. Destinations that have heavily relied on tourism can develop more holistic, resilient and sustainable tourism models that are based on local knowledge and wisdom, local ownership and collaboration with other sectors (i.e agriculture and aquaculture, etc). Dr. Mahyuni noted that there will be more opportunities for locals to improve and run their own businesses as local people start re-appreciating and valuing their natural resources and culture (e.g. agri-tourism).

Citing India as an example, Dr. Kiran Shinde noted that many ashrams and monasteries are not designed for domestic tourism, and many are owned and run by foreigners. Often, even the meditation teachers are foreign. This is due, in part, to how spiritual and wellness tourism phenomenon has developed so quickly that local people have not had the time, space and resources to build their capacity to own and manage those businesses. Under current circumstances, local people often have low paid jobs in yoga and meditation tourism businesses. The pandemic might give people the opportunity to step into this form of tourism, albeit in a small way.

There is some evidence to suggest that there might be the initial revival in luxury wellness tourism (i.e. luxury yoga retreats), as destinations in South and Southeast Asia seek smaller numbers of wealthy tourists to remedy the economic damage. Those seeking a budget and affordable opportunities may be left out, which would be detrimental to those without the wallet to afford ‘wellness.’ This trend is also detrimental to those local businesses who cater for these tourists and who can’t access the investment to cater for the wealthy and their demands for space and social distancing. Dr. Shinde mentioned that ‘normal’ domestic tourists in India can’t take time off and don’t have the money and resources to visit meditation retreats. Those programmes are really for local elites and foreigners.

There must be local government support for small and local-owned enterprises to cater for all budgets and backgrounds, as well as support for local wellness products. This COVID-19 and post pandemic period can be a time to not only self-reflect on the meanings of life, but also reflect for the whole tourism system and the opportunities it can offer for a more accountable, equitable and transparent industry. Whilst there are indications that planners, marketers and businesses are trying to get back to ‘business as usual,’ the pandemic provides a time to pause and self-reflect.

There are many complexities and uncertainties in front of us, but I hope that this time will engender more community-based, holistic, decentralised and positive tourism futures. At least, I will meditate on it.

Originally from Korea, Dr. Jaeyeon Choe is a Senior Lecturer at Bournemouth University, UK. She is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and co-editor of a book Pilgrimage Beyond the Officially Sacred: Understanding the Geographies of Religion and Spirituality in Sacred Travel (Routledge 2020). She has written and spoken about spiritual and wellness tourism primarily in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia and Thailand. She keynoted at the Sustainable Tourism Development for Southeast Asia Conference in Vietnam in December 2019. She moderated the webinar, “Wellness and spiritual tourism in a post COVID-19 world?” on June 13th, 2020, which is accessible on YouTube.